Brent

points to Bell and Newby, who see community as a paradox, in which “as soon as

one tries to define it, it ceases to have a verifiable existence” and questions if, as some posit, that community is just an

illusion (219). While Brent is not responding to community in an online classroom

environment, there are parallels, as community is discussed in teaching pedagogy

time and again (Warnock, Neff, Cook, Garrison and Vaughan). Is it an illusion

in an online classroom? Can it be developed and replicated from one class to

another, much like course content? I would argue that the answer is no, that

community is not a product that an instructor can create within an online or

face-to-face class, but rather it is a mix of time, space and participants–coaxed

and encouraged--but with an existence uniquely its own depending on the

motivation and engagement of the class.

In our blogs, as individual

articles were shared and analyzed, we had the opportunity to read exponentially

more material and be exposed to many more authors than we would have been if we

would not have posted our information communally. I analyzed the topics

and sources used [Appendix], identifying 44 unique sources. Of these, only four sources were used more

than once, with only one source used more than twice (nine times). Of 55 total references, there was only one duplicate

reference posted [figure 1]. |

Source Title

|

# articles

|

|

Computers and Composition

|

9

|

|

British Journal of Educational Technology

|

2

|

|

Computers & Education

|

2

|

|

Journal of Library Administration

|

2

|

|

Adult Learning

| |

|

College Composition and Communication

| |

|

College English

| |

|

Educational Technology Research and Development

| |

|

English Education

| |

|

IALLT Journal

| |

|

Innovative Higher Education

| |

|

Instructional Science: an International Journal of the Learning Sciences

| |

|

International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative

Learning

| |

|

International Journal or E-Learning & Distance Education

| |

|

Journal of Agricultural Education

| |

|

Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks

| |

|

Journal of Basic Writing

| |

|

Journal of Educational Technology

| |

|

Journal of Educational Technology & Society

| |

|

Journal of Global Intelligence & Policy

| |

|

Journal of Information Technology Education

| |

|

Journal of Interactive Online Learning

| |

|

Journal of Public Affairs Education

| |

|

Journal of Technical Writing & Communication

| |

|

Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning

| |

|

Journal of Writing Research

| |

|

Kairos

| |

|

New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education

| |

|

Nurse Educator

| |

|

Pedagogy

| |

|

Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences

| |

|

Research and Teaching in Developmental Education

| |

|

Rocky Mountain Review

| |

|

Teaching English in the Two-Year College

| |

|

TESL Canada Journal

| |

|

TESL-EJ

| |

|

TETYC

| |

|

The International Review of Research in Open and Distance

Learning

| |

|

The Internet and Higher Education

| |

|

The Journal of Higher Education

| |

|

The Journal of Midwest Modern Language Association

| |

|

The Journal of Nursing Education

| |

|

Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology

| |

Figure 1: Journal

Usage. Student Blogs, ENG 824 (Summer 2014)

Individual students’ research interests were pursued, with

very little overlap on the surface, but when keyword tags were applied to the articles,

there were similarities in the overall themes, as illustrated in a word cloud

[figure 2].

|

| Figure 2: Key Terms in Article Titles/Subjects |

The purposes for our blogs were outlined in the syllabus: 1) Supplement the assigned readings and have the opportunity to research on the topic(s) that we will focus on for course projects. 2) Writing experience and practicing the production of scholarship within the discourse community of writing studies and distance education. 3) Writing to learn exercise in which the process of writing up the blog entry helps you understand the content and how to articulate this understanding to the discourse community. These all encourage research and individual exploration as part of the “discourse community of writing studies and distance education.” An academic community, focusing on scholars interested in a specific area of scholarship, further establishes my claim that communities may be self-selected or offered, but that participation best comes from internal motivation.

How do communities develop within a class? Community building techniques need to be “explicitly explained” in a distance class as to their purpose (Neff 85). While explanations of purpose at an undergraduate level may be needed for “modeling an intellectual community,” this should not have to be explained at the graduate level, as I posit that the purpose of blogging or other asynchronous discussion forums are more than a tool to create class community [1], as students may use these spaces for different purposes and community-building may only be a peripheral benefit. Garrison and Vaughan point constructivist learning theory, in which individuals are “making sense of their experiences” with “inquiry at its core” (13-14). We each had autonomy in our blog subject matter, with broad latitude applied to the interest areas we chose to explore. Pointing to the necessity of students being “actively engaged in the process of inquiry,” with a community of inquiry (CoI) as a method to achieve this, our class blogs could be viewed as both CoI and applied constructivism.

Neff looks to asynchronous communication as created spaces “where students can control the direction of the conversation in ways that they cannot in traditional educational classrooms” (93). She stresses that “learning is enhanced when it is more like a team effort than a solo race. Good learning like good work is collaborative and social, not competitive and isolated. Working with others increases involvement in learning. Sharing one’s ideas and responding to others improves thinking and deepens understanding” (Gamson as cited in Neff 100). Encouragement can also be given for students to use online posting avenues outside single assignments by drawing the content in to other discussions, encouraging students to continue participation, noting that instructors should not be “the bottleneck” and that low-stakes writing often encourages better participation if students aren’t always just writing with assessment in mind or for a particular assignment (Warnock 83).

While graduate students may use blogging for their own research purposes without external motivation, I have used both ungraded and graded blog posts/comments in numerous undergraduate online classes, without clear guidelines as to when, what and how much to post and undergraduate students, in my experience, will usually only post to the requirements. Warnock points to the benefit of assigning primary and secondary posts, with a discussion around the necessity of outlining the expectations and timing for when students should post to encourage active participation, but recognizing that a reward/punishment system will change how posts are perceived within a class. In our class, by having blog posts due at certain times, but with no expectation of what follow-up comments or conversations might ensue from the posts, it was left open to interpretation and posts only appeared sporadically, but never became a major place of conversation within the class.

Requiring comments on a blog will elicit increased response, as students are often grade motivated, but is commenting on a blog building community or just increasing forced participation – a form of the medicine that is good for you? Warnock focuses on conversation and asynchronous message boards as being a “cornerstone” of his own online pedagogy with a goal of wanting students to “talk with one another” (68). Focusing conversations on students and their responses, Bakhtin points to the response as being the foundation of understanding, rather than teachers talking “to” students (as cited in Warnock 68) it pushed us to think in new ways about active learning and student agency in their own learning.

By having students

create their own space and not using a centralized or CMS space to post, students

are offered more personal agency in their work.

I spent time deciding how I wanted my blog to appear, knowing it would

reflect on me, as it was not the result of content created by a course designer

or instructor. Was this an articulated

purpose of our blog? No, but as Garrison

and Vaughan point out, it may be the “unintended learning outcomes [that] can

be most educational” (21). Most of the members of our class use their blogs for

other classes and see them as continuing spaces, part of their doctoral studies

and a repository of their work. Both as

archival information and a channel to share readings and responses with

classmates, this is a different type of community than what undergraduates

would experience with a one class requirement, unless there were collaborative

efforts to use blogs as a cross-curricular portfolio to document writing

development.

On our blogs, only one student

received a public comment, but in other classes I have taught, I have had

students surprised when their blog receives comments from the blogosphere. Using a blog as a rhetorical space helps to teach

how a digital environment has an audience that must be considered and

acknowledged in a public writing forum. Depew et al. express that “communities

are not an outcome that instructors simply can create by using a specific digital

technology” as “creating community is a rhetorical act deliberately attempted.”

In questioning the efficacy of a blog to create community within an online

class, I would posit that while the instructor can offer ways for interactions

to occur within as classroom and encourage participation, short of requiring

postings, it is also the students’ responsibility and/or motivation to want the

community of their peers.

As

in a face-to-face classroom, some students may just want to attend class and complete

the assignments. In a 1997-2002 review

of the Temple University Online Learning

Program, findings showed that professor interaction was significantly more

important to students than was classmates’ interaction (Schifter 174). One

student noted that while acknowledging a “high level of interactivity among the

student and other classmates” that it was “difficult for me, however, to get

any kind of personal feeling for any of the students” (Schifter 177). Is this by choice or a construct of the

online environment, as those survey questions were not part of the Temple

review?

In

the case of our class blog, my motivation for reading and posting to others’

blogs was intellectually, rather than grade motivated. I wanted to learn more

about the subjects studied in the class and my classmates’ research interests. As a new doctoral student, inquiry and

research are stressed within our curriculum and expected. That is not the same

level of expectation placed on undergraduates who may not have this internal

motivation. Warnock’s Guidelines 21-25 for

Teaching Writing Online focus on conversations and use of asynchronous message

boards, pointing out how they provide “powerful and effective writing and

learning environments” noting that the instructors have a chance to not be the

focus of the conversation or be directly involved, letting students direct what

happens (75).

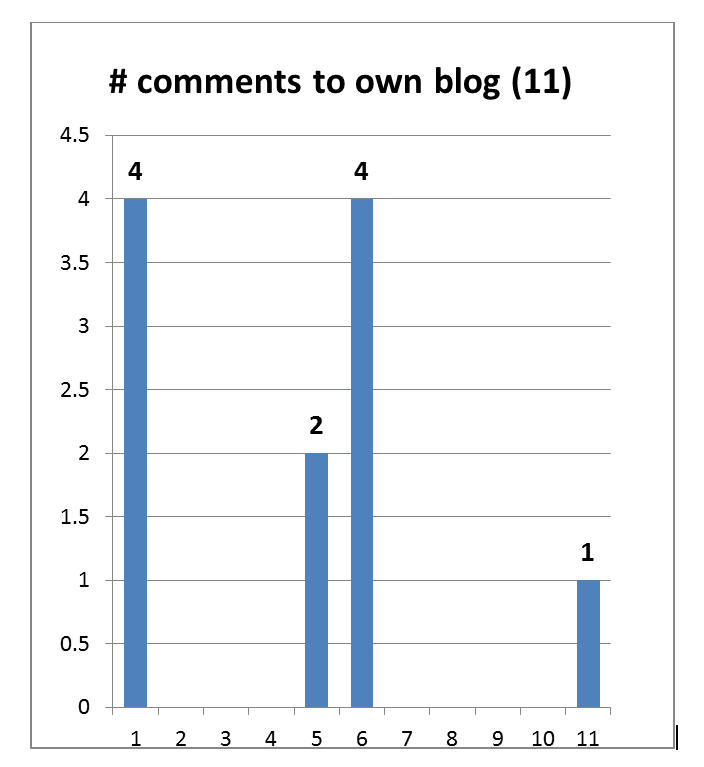

|

Figure 3: Total Comments to

Student Blogs

|

|

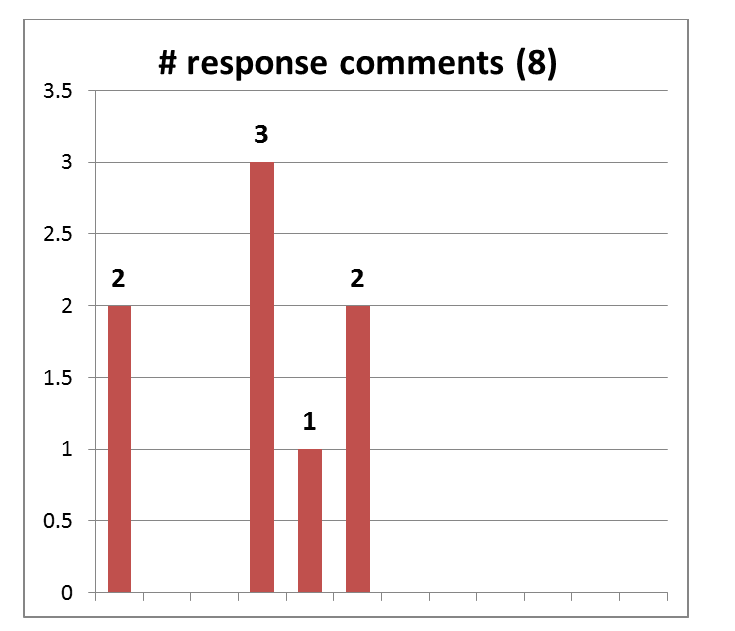

| Figure 4: Response Comments to Student Blogs |

While echoing the concerns of CCCC OWI Position Statement’s second principle, “an online writing course should focus on writing and not on technology orientation or teaching students how to use learning and other technologies,” the benefit of a blog and having students actively participate in their own learning is valuable. I have had students express the benefits of posting in my classes, but also wish they had their own space to post to where they could create their own online presence. Recognizing that a blog has rhetorical elements and using that discussion as part of a class is also beneficial, as DePew notes, it isn’t about “using” a technology, but recognizing “what does this technology want me to do?” and how can its affordance be of benefit to student learning within an online classroom? Each technology “demands” something from a user, and it is important that this is recognized as part of assigning a technology, such as a blog.

I

return to Brent’s original questions asking what is community and if it is an

illusion? In an online classroom,

instructors can optimize learning opportunities and establish a framework by

which students may elect to or not to participate, but those attempts do not

necessarily translate to community building.

That is up to individuals in a class and each student’s motivation, as “participants

must have the discipline to engage in critical reflection and discourse” (Garrison

and Vaughan 17). Ultimately community is

possible, it is not an illusion, but neither is it a contrived space or place.

Rather, it is one that develops organically as students strive to make

connections and desire to move beyond

just participation for a grade.

Works

Cited

Brent, Jeremy. "The Desire for Community: Illusion,

Confusion and Paradox." Community Development Journal 39.3 (2004):

213-23.

Cook, Kelli Cargile. "An Argument for Pedagogy-Driven

Online Education." Online Education: Global Questions, Local Answers. Amityville, NY: Baywood Publishing Co., Inc.

2005. 49-66.

DePew, Kevin Eric. "Preparing Instructors and

Students for The Rhetoricity of OWI Technologies." Foundational

Practices of Onine Writing Instruction. Eds. Beth Hewett and Kevin Eric

DePew. Publication Forthcoming 2014.

Garrison, D. Randy and Norman D. Vaughan.

"Introduction." Blended Learning in Higher Education: Framework,

Principles, and Guidelines. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2007. 3-11.

Neff, Joyce Magnotto

and Carln Whithaus. Writing across

Distances & Disciplines: Research and Pedagogy in Distributed Learning. New

York: Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc., 2007.

Schifter, Catherine. “Evaluating

a Distance Education Program.” [Ch. VII]. The

Distance Education Evolution: Issues and Case Studies. Eds. Dominique

Monolescu, Catherine Schifter, and Linda Greenwood. Hershey, PA: Science

Publishing, 2004. 163-184.

Warnock, Scott. Teaching Writing Online: How & Why.

Urbana, IL: NCTE, 2009.

& & &

APPENDIX:

|

ID

|

Source Reference

|

Keywords

|

|

1

|

Gouge, C. (2009).

“Conversation at a crucial moment: Hybrid courses and the future of writing

programs.” College English, 71(4),

338-362.

|

Online Writing Instruction

Rehabilitation Counseling Students

Multi-literacies

Hybrid Courses

Digital Writing

Participation

|

|

Rendahl, M.A. (2009). “It’s

not the Matrix: Thinking about online writing instruction.” The Journal of Midwest Modern Language

Association, 42(1), 133-150

|

||

|

Grabill, J.T. & Hicks,

T. (2005). “Multi-literacies meet methods: The case for digital writing in

English education.” English Education,

37(4), 301-311.

|

||

|

Harrington, A. M. (2010).

“Hybrid developmental writing courses: Limitations and alternatives.” Research and Teaching in Developmental

Education, 26(2), 4-20.

|

||

|

Warnock, S., Bingham, K.,

Driscoll, D., Fromal, J., & Rouse, N. (2012). “Early participation in

asynchronous writing environments and course success.” Journal of Asynchronous Learning

Networks, 16(1), 35-47.

|

||

|

Main, D., & Dziekan, K.

(2012). “Distance education: Linking traditional classroom rehabilitation

counseling students with their colleagues using hybrid learning models. Rehabilitation

Research, Policy and Education,

26(4), 315-320.

|

||

|

2

|

Burgess,

Kimberly R. "Social Networking Technologies as Vehicles of Support for

Women in Learning Communities." New Directions for Adult and

Continuing Education. 122

(2009): 63-71.

|

Social

Networking

Women

Online

Writing Classroom

Nursing

Blended

Learning

Connecting

with Students

Anonymity

Supportive

Presence

|

|

Griffin,

June, and Deborah Minter. "The Rise of the Online Writing Classroom:

Reflecting on the Material Conditions of College Composition Teaching." College

Composition and Communication. 65.1 (2013): 140-161.

|

||

|

Stevens,

Carol J., et al. "Implementing a Writing Course in an Online RN-BSN

Program." Nurse Educator 39.1 (2014):17-21.

|

||

|

Miyazoe,

Terumi, and Terry Anderson. "Anonymity In Blended Learning: Who Would

You Like To Be?" Journal of Educational Technology & Society

14.2 (2011): 175-187.

|

||

|

Diekelmann,

Nancy, and Elnora P. Mendias. "Being a Supportive Presence in Online

Courses: Knowing and Connecting with Students through Writing." The

Journal of Nursing Education 44.8

(2005): 344-346.

|

||

|

3

|

Shultz Colby, Rebekah. "A Pedagogy of Play: Integrating

Computer Games into the Writing Classroom." Computers and Composition

25. Reading Games: Composition, Literacy, and Video Gaming (2008):

300-312.

|

Computer Games

Writing Classroom

Rhetoric

Adult Learners

Pedagogy

Community

Social Media

Digital Imperative

Student Learning

Online Discussions

Academic Performance

|

|

Ewing, Laura A. "Rhetorically Analyzing

Online Composition Spaces." Pedagogy 3 (2013): 554-560.

|

||

|

Blair, Kristine, and Cheryl Hoy. "Paying

Attention to Adult Learners Online: The Pedagogy and Politics of

Community." Computers & Composition 23.1 (2006): 32-48.

|

||

|

LeNoue, Marvin, Tom Hall, and Myron A. Eighmy.

"Adult Education and the Social Media Revolution." Adult

Learning 22.2 (2011): 4-12.

|

||

|

Clark, J. Elizabeth. "The Digital Imperative:

Making the Case for a 21st-Century Pedagogy." Computers & Composition 27.1 (2010): 27-35.

|

||

|

4

|

Lee,

S.W.Y. (2013). Investigating students' learning approaches, perceptions of

online discussions, and students' online and academic performance. Computers

& Education, 68,

345-352.

|

Student

Learning

Online

Discussions

Academic

Performance

Asynchronous

Discussions

Scaffolding

Academic

Engagement

Mediation

Roles

Goals

Cognitive

Engagement

First

Year Writing

|

|

Hew, K. F., Cheung, W. S., & Ng, C. S. L.

(2010). Student contribution in asynchronous online discussion: A review of

the research and empirical exploration. Instructional Science: an

International Journal of the Learning Sciences, 38(6),

571-606.

|

||

|

Cho, M.H., & Cho, Y. J. (2014). Instructor

scaffolding for interaction and students' academic engagement in online

learning: Mediating role of perceived online class goal structures. The Internet and Higher Education, 21(3),

25-30.

|

||

|

Shukor, N. A., Tasir, Z., Van, M. H., &

Harun, J. (2014). A Predictive Model to Evaluate Students’ Cognitive

Engagement in Online Learning. Procedia

- Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 4844-4853.

|

||

|

Rendahl, M., & Breuch, L. A. (2013). Toward a Complexity

of Online Learning: Learners in Online First-Year Writing. Computers

and Composition, 30(4),

297-314.

|

||

|

5

|

Hargis,

J., Cavanaugh, C., Kamali, T., & Soto, M. (2014). A Federal Higher

Education iPad Mobile Learning Initiative: Triangulation of Data to Determine

Early Effectiveness. Innovative Higher Education, 39(1), 45-57.

doi:10.1007/s10755-013-9259-y

|

Innovation

iPad

Mobile

Learning

Effectiveness

Writing

Scrivener

Tools

Word

Processing

Kindle

Writing

Classroom

Higher

Education

Mobile

Tablets

Google

Drive

Blended

Learning

Authentic

Learning

|

|

Bray,

N. (2013). Writing with Scrivener:

A hopeful tale of disappearing tools, flatulence, and word processing

redemption. Computers and Composition, 30(3), 197-210. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2013.07.002

|

||

|

Acheson,

P., Barratt, C. C., & Balthazor, R. (2013). Kindle in the writing

classroom. Computers and Composition, 30(4), 283-296. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2013.10.005

|

||

|

Rossing,

J. P., Miller, W. M., Cecil, A. K., & Stamper, S. E. (2012). iLearning:

The future of higher education? Student perceptions on learning with mobile

tablets. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning, 12(2), 1-26.

|

||

|

Rowe,

M., Bozalek, V., & Frantz, J. (2013). Using Google Drive to facilitate a

blended approach to authentic learning: Authentic learning and Google Drive. British Journal of Educational

Technology, 44(4), 594-606. doi:10.1111/bjet.12063

|

||

|

6

|

York, Amy C., and Jason M. Vance.

"Taking Library Instruction into the Online Classroom: Best Practices

for Embedded Librarians." Journal of Library Administration 49.1/2 (2009): 197-209.

|

Library Instruction

Embedded Librarians

Online Classroom

Hybrid Classroom

ESL/EFL

Library Resources

Library Services

International

Global

Personal Touch

Library Faculty

English

|

|

Harrington,

Anna M. “Problematizing the Hybrid Classroom for ESL/EFL Students.” TESL-EJ 14.3 (December 2010): 1-13.

|

||

|

Wang,

Zhonghong and Paul Tremblay. “Going Global: Providing Library Resources and

Services to International Sites.” Journal

of Library Administration 49 (2009): 171-185.

|

||

|

Zhang,

Jie. “Learner Agency, Motive, and Self-Regulated Learning in an Online ESL

Writing Class.” IALLT Journal 43.2

(2013): 57-81

|

||

|

Kadavy,

Casey, and Kim Chuppa-Cornell. "A Personal Touch: Embedding Library

Faculty into Online English 102." TETYC

39.1 (2011): 63-77.

|

||

|

7

|

Yang, Yu-Fen. "A Reciprocal Peer Review

System to Support College Students' Writing." British Journal of Educational Technology 42.4 (2011): 687-700.

|

Peer Review

College Writing

Students

Online Writing Classroom

Adaptation

Training

Workshop

Evaluation

Assessment

Revision Process

Collaborative Writing

|

|

Knight,

Linda V., and Theresa A. Steinbach. "Adapting Peer Review to an Online

Course: An Exploratory Case Study." Journal

of Information Technology Education 10 (2011): 81-100.

|

||

|

Lam, Ricky. "A Peer Review Training

Workshop: Coaching Students to Give and Evaluate Peer Feedback." TESL Canada Journal 27.2 (2010):

114-27.ERIC. Web. 31 May 2014.

|

||

|

Goldin, Ilya M., and Kevin D. Ashley.

"Eliciting Formative Assessment in Peer Review." Journal of

Writing Research 4.2 (2012): 203-27.

|

||

|

Woo, Matsuko Mukumoto, Samuel Kai Wah Chu, and

Xuanxi Li. "Peer-feedback and Revision Process in a Wiki Mediated

Collaborative Writing." Educational Technology Research and

Development 61.2 (2013): 279-309. Web. 27 May 2014

|

||

|

8

|

Arslan,

R. (2014). Integrating feedback into prospective English language teachers'

writing process via blogs and portfolios. Turkish Online Journal of

Educational Technology, 13(1),

131-150.

|

Feedback

Blogs

Portfolios

Scaffolding

Collaboration

Technical

Writing

Synchronous

Discussion

Facilitation

Agricommunication

Web

Instruction

Attitudes

Service

Learning

Distance

Education

|

|

Yeh,

S., Lo, J., & Huang, J. (2011). Scaffolding collaborative technical

writing with procedural facilitation and synchronous discussion. International

Journal Of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 6(3), 397-419.

|

||

|

Day,

T.M., Raven, M.R. & Newman, M.E. (1998). The Effects of World Wide Web

Instruction and Traditional Instruction and Learning Styles on Achievement

and Changes in Student Attitudes in a Technical Writing in Agricommunication

Course. Journal of Agricultural

Education,39(4), 65-75.

|

||

|

Ya

Ni, A. (2013). Comparing the Effectiveness of Classroom and Online Learning:

Teaching Research Methods. Journal Of Public Affairs Education, 19(2), 199-215.

|

||

|

Soria,

K. M., & Weiner, B. (2013). A "Virtual Fieldtrip": Service

Learning in Distance Education Technical Writing Courses. Journal Of

Technical Writing & Communication, 43(2), 181-200. doi:10.2190/TW.43.2.e

|

||

|

9

|

Chen, Pu-Shih Daniel, Amber D. Lambert, and Kevin

R. Guidry.“Engaging online learners: The impact of Web-based learning

technology on college student engagement.” Computers & Education 54 (2010): 1222-1232.

|

Engagement

Online Learners

Web

Writing

Online Composition

Ecologies

First Year

Persistence

Web-Based Writing

Technologies

Complexity

Blending

|

|

Gillam, Ken and Shannon R. Wooden. “Re-embodying

Online Composition: Ecologies of Writing in Unreal Time and Space.” Computers

and Composition 30.1 (2013): 24-36.

|

||

|

Kuh, George D. et. al. “Unmasking the Effects of

Student Engagement on First-Year College Grades and Persistence.” The

Journal of Higher Education 79.5 (2008): 540-563.

|

||

|

Gouge, Catherine. “Writing Technologies and the

Technologies of Writing: Designing a Web- Based Writing Course.” Kairos 11.2

(2007).

|

||

|

Rendahl, Merry and Lee-Ann Kastman Breuch.

“Toward a Complexity of Online Learning: Learners in Online First-Year

Writing.” Computers and Composition 30.4 (2013): 297-314.

|

||

|

10

|

Wach, Howard, Laura Broughton, and

Stephen Powers. “Blending in the Bronx: The Dimensions of Hybrid Course

Development at Bronx Community College.” Journal

of Asynchronous Learning Networks 1 (2011): 87.

|

Community College

Hybrid

Course Development

Multi-Modalities

Engaged Learners

Composition

21st Centuryt

Developmental Writers

Conversations

Online Learning

Basic Writing

Web-Enhanced

Environments

|

|

Gillam, Ken, and Shannon R. Wooden. “Re-Embodying

Online Composition: Ecologies of Writing in Unreal Time and Space.” Computers

and Composition 30. Writing on the Frontlines (2013): 24-36.

|

||

|

Arms, Valarie M. “Hybrids, Multi-Modalities and Engaged

Learners: A Composition Program for the Twenty-First Century.” Rocky

Mountain Review 2 (2012): 219.

|

||

|

Stine, Linda. “Basically Unheard: Developmental Writers

and the Conversation on Online Learning.” Teaching English in the Two-Year

College 38.2 (2010): 132-148.

|

||

|

Stine, Linda J. “Teaching Basic

Writing In A Web-Enhanced Environment.” Journal Of Basic Writing 29.1

(2010): 33-55.

|

||

|

11

|

Mandernach,

Jean B., Amber Dailey-Herbert, and Emily Donnelli-Sallee. “Frequency and Time

Investment of Instructors’ Participation in Threaded Discussions in the

Online Classroom.” Journal of Interactive Online Learning 6.1 (2007). 1-9.

|

Instructors

Participation

Online

Classroom

Rapport

Distance

Education

Relationships

Facilitating

Reflection

Interactivity

Writing

Online

Course

Qualitative

Study

Twitter

Test

Assessing

Outsomes

Student

Collaboration

Engagement

Success

|

|

Murphy,

Elizabeth and Maria A. Rodriquez-Manzanares. “Rapport in Distance Education.”

The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 13.1 (Jan 2012). 167-190.

|

||

|

Conner,

Tonya. “Relationships First.” Journal of Global Intelligence & Policy

6.11 (2013). 37-41.

|

||

|

Andrusyszyn

, Mary-Anne and Lynn Davie.

“Facilitating Reflection through Interactive Journal Writing in an Online

Graduate Course: A Qualitative Study.” International Journal or E-Learning &

Distance Education 12.1 (1997). 103-126.

|

||

|

Junco,

Reynal, C. Michael Elavsky, and Greg Heiberger. “Putting Twitter to the Test: Assessing Outcomes for

Student Collaboration, Engagement and Success.” British Journal

of Educational Technology 44.2 (2013): 273-287.

|